The Bible’s 40 Authors: An Overview

The Bible is a collection of 66 books from 40 authors. It was compiled around 400 AD by various church councils, who selected the books that would be part of it.

The Core Claim: Divine Inspiration Through Diverse Hands

A core claim surrounding the Bible’s composition posits its profound divine inspiration, manifested uniquely through the writings of numerous and diverse human authors. Many Christians believe that God intentionally used approximately 40 distinct individuals to pen the sacred texts. These chosen authors, regardless of their personal backgrounds or professions, were not merely recording their own thoughts or opinions but were profoundly guided by the Holy Spirit to convey God’s own message. This perspective asserts that Jehovah himself is the ultimate author, with the human writers serving as faithful instruments of His divine will. The belief is that despite the varied historical contexts and diverse perspectives of these forty-plus human authors, their collective work forms a divinely coherent and truly inspired Word. The sheer number of distinct voices contributing to the Bible is often highlighted as compelling evidence of a miraculous, overarching divine hand, ensuring a harmonious and unified journey through time. This remarkable alignment, spanning different centuries, continents, and languages, is attributed solely to God’s direct communication and meticulous oversight, transforming individual human efforts into a singular testament of divine truth. This foundational idea powerfully emphasizes God’s direct involvement in shaping the scriptures through human vessels, creating a unified narrative.

Number of Authors and Books

The Bible, a monumental collection of sacred texts, is composed of a remarkable 66 individual books. This extensive library of writings was not the product of a single individual, but rather the collaborative effort of approximately 40 distinct authors. These 40 known authors contributed to the diverse literary forms and historical accounts found within the biblical canon. It is consistently stated that the Bible comprises 66 books, penned by around 40 different individuals. This specific number of authors highlights the breadth of perspectives and life experiences woven into the fabric of scripture. The compilation process, occurring around 400 AD through various church councils, brought these 66 books together. The consistent enumeration of 40 authors and 66 books across various sources reinforces this foundational understanding of the Bible’s structure. This multiplicity of writers, yet singular collection of books, forms a unique literary and spiritual testament. The fact that roughly 40 faithful men were employed by God to write these texts underscores the diverse human involvement in transmitting divine messages. This numerical framework is a key characteristic of the Bible’s composition, emphasizing its comprehensive and multi-faceted nature; The 66 books are divided into the Old and New Testaments, each reflecting the contributions of these numerous authors, culminating in a complete scriptural record.

Traditional Christian View of Authorship

The traditional Christian view of authorship posits the Bible as divinely inspired, with God as its ultimate author. It is widely held that approximately 40 distinct individuals, chosen by God over many centuries, served as human instruments for penning the 66 books. This perspective asserts that these writers recorded God’s thoughts, not merely their own ideas. For example, traditional accounts credit Moses with writing the first five books, the Pentateuch, around 3,500 years ago. The Apostle John, similarly, is recognized for authoring the last book, Revelation, over 1,900 years ago. This vast temporal span and diversity of human authors are highlighted as a testament to the Bible’s miraculous unity and divine origin. Despite their varied backgrounds and historical contexts, these numerous writers are believed to have consistently conveyed a single, central message, forming a coherent narrative. The Holy Spirit directed them, ensuring the accurate transmission of God’s infallible Word. This foundational belief underscores the conviction that the Bible is uniquely authoritative, representing God’s direct communication to humankind through carefully selected individuals. This harmonious testimony across ages is central to its traditional understanding.

God’s Communication with Bible Writers

God’s communication with the Bible writers is a cornerstone of its divine authorship. According to traditional Christian understanding, God did not merely inspire general ideas but directly conveyed His message to the approximately 40 human authors. This profound interaction primarily occurred through the Holy Spirit. The writers were not simply expressing their own opinions or reflections; rather, they were guided and directed to transcribe God’s very thoughts and words. This process ensured that the resulting texts accurately reflected the divine will and purpose. Jehovah’s Witnesses, for instance, explicitly state that Jehovah is the ultimate author, as these men penned His words under supernatural direction. The human element was present in their individual styles and personalities, yet the content remained God-breathed. This form of communication transcended ordinary human composition, making the Bible uniquely distinct. The Holy Spirit acted as the divine conduit, empowering these diverse individuals—from kings and prophets to fishermen and physicians—to record sacred truths. Their role was to faithfully document divine revelations, prophecies, laws, and narratives, ensuring a consistent and authoritative message across millennia. This divine oversight guarantees the Bible’s reliability and its profound spiritual depth, serving as God’s direct voice to humanity.

The Role of the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit played an indispensable role in the authorship of the Bible, serving as the divine orchestrator behind its creation. It was through the Holy Spirit that God communicated directly with the approximately 40 human writers. These individuals, despite their diverse backgrounds and historical contexts, were not merely offering their personal insights or theological reflections. Instead, they were divinely empowered and guided, writing down “the thoughts of God, not their own thoughts.” This supernatural direction ensured the authenticity and infallibility of the biblical texts. As Jehovah’s Witnesses affirm, the Holy Spirit’s guidance means that Jehovah is the ultimate author, with human hands simply serving as instruments. The Spirit directed them in what to write, how to articulate divine truths, and even which historical events and prophecies to record. This process is often described as “inspiration,” where God “breathed out” His word through human agents. Consequently, the unity and coherence observed across the 66 books, spanning various genres and centuries, are attributed to the singular influence of the Holy Spirit. This divine inspiration guarantees that the Bible truly represents God’s authoritative message to humanity, free from human error in its original form. The Spirit’s role was central to transforming human thoughts into God’s eternal word.

Jehovah as the Author

Jehovah is consistently presented as the true and ultimate author of the Bible, a perspective strongly maintained by groups like Jehovah’s Witnesses. While approximately 40 different individuals penned the various books, they are regarded not as independent creators but as divinely guided scribes. These faithful men, spanning centuries and diverse backgrounds, acted as conduits for a singular divine message. The core belief is that God communicated His thoughts and instructions to these writers, who then recorded precisely what He intended, rather than their own personal opinions or interpretations.

This understanding means that the Bible’s inherent authority and unified message stem directly from its divine source, Jehovah. The human authors were merely instruments in His hand, entrusted with the sacred task of transcribing His eternal word. For instance, the first five books are traditionally attributed to Moses, written millennia ago, and the final book to the Apostle John, yet the underlying authorship remains with Jehovah. This ensures that the entire collection, from Genesis to Revelation, carries the weight of divine truth. The writers “wrote down His words as the Holy Spirit directed them,” solidifying the conviction that the entire scripture is “God-breathed.” This perspective elevates the Bible beyond a human literary work, establishing it as the direct communication from the Sovereign Author to humanity. It’s a testament to divine oversight, ensuring consistency across the diverse compilation.

Timeline of Writing: Traditional Perspective

From a traditional Christian viewpoint, the Bible’s composition spans an impressive historical arc, reflecting God’s sustained communication with humanity across millennia. This perspective posits that approximately 40 distinct individuals contributed to the sacred texts over a vast period of about 1500 years. The journey of its writing is traditionally believed to have commenced with Moses, who, around 3,500 years ago, is credited with authoring the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament. These foundational narratives lay the groundwork for Israel’s history, law, and covenant relationship with God.

The compilation continued through various prophets, kings, and scribes, documenting significant events, prophecies, psalms, and wisdom literature. This centuries-long process culminated with the Apostle John, who, over 1,900 years ago, penned the final book of the New Testament, Revelation. This book offers prophetic visions concerning the end times and the ultimate triumph of God’s kingdom. Therefore, the traditional timeline emphasizes a continuous, divinely orchestrated unfolding of scripture, bridging ancient history to the early Christian era, resulting in a cohesive collection despite the extended period and numerous human hands involved. This long duration underscores the enduring nature of God’s message and His consistent engagement with His people throughout different historical contexts.

Moses and the First Five Books

Moses is traditionally credited with authoring the Pentateuch, comprising Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. These first five books, believed written by him approximately 3,500 years ago, establish Moses as a foundational human writer. As the leader of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, he was uniquely positioned to record these narratives.

The Pentateuch details creation, humanity’s origins, and God’s covenant with Abraham. It recounts Israel’s liberation from slavery, their wilderness journey, and the reception of the Law at Mount Sinai. Beyond history, these books contain essential theological principles, legal codes, and moral guidelines for the Israelite nation. Moses’ role as the divinely appointed mediator underscores his profound importance. His authorship forms the bedrock for the Old Testament, providing its comprehensive origin story and fundamental legal framework for the entire biblical canon.

Apostle John and the Last Book

The Apostle John is traditionally recognized as the author of the Bible’s final book, Revelation. This powerful prophetic work, also known as the Apocalypse, was written over 1,900 years ago, making it one of the last contributions to the biblical canon. John, one of Jesus’ closest disciples, received these profound visions while exiled on the island of Patmos. His account details future events, including Christ’s return, the final judgment, and the establishment of a new heaven and new earth.

Revelation serves as a climactic conclusion to the entire biblical narrative, bringing together themes of creation, redemption, and ultimate divine victory. John’s unique perspective, having witnessed Jesus’ ministry firsthand and later experiencing these profound revelations, lends immense spiritual weight to his writing. The book is rich with symbolic language and imagery, offering hope and warning to believers across generations. It underscores the enduring message of God’s sovereignty and His ultimate plan for humanity, solidifying its place as a cornerstone of Christian eschatology. John’s contribution provides a powerful, future-oriented perspective that caps the diverse collection of biblical writings. His authorship of this final text brings the overarching story of divine interaction with humanity to its ultimate, triumphant close.

The Bible’s Geographical and Linguistic Diversity

The Bible’s remarkable composition showcases an extraordinary tapestry of geographical and linguistic origins, a testament to its universal appeal and enduring relevance. Its sixty-six books were penned across three distinct continents: Asia, Africa, and Europe. This vast geographical spread meant that authors from diverse cultures and historical eras contributed to the sacred texts, ensuring a broad perspective that transcends any single regional viewpoint.

Linguistically, the Bible’s original writings encompass three primary ancient languages. The majority of the Old Testament was written in Hebrew, the foundational language of the Israelite people. Specific portions, notably in books like Daniel and Ezra, were composed in Aramaic, a Semitic language widely spoken in the Near East. The New Testament, recording the life of Jesus and the early Christian church, was originally written in Koine Greek, the common language of the Hellenistic world. This linguistic diversity highlights the Bible’s ability to communicate profound truths across varied cultural and intellectual landscapes, uniting a complex narrative through a multitude of voices and tongues.

Scholarly Perspectives on Authorship and Editing

Scholarly perspectives on the Bible’s authorship and editing offer a nuanced view that often contrasts with singular traditional interpretations. Modern academic research, employing critical methodologies, suggests a more complex developmental history for the biblical texts. For instance, the renowned Documentary Hypothesis posits that the Old Testament, particularly the Torah, was not solely the work of a single author. Instead, it was compiled from multiple sources and underwent significant continuous re-editing and modification over centuries, spanning approximately 500 years from its inception around 1000 BCE. This scholarly analysis indicates that the texts evolved through various editorial hands, with different authors contributing and redacting material. Recent advancements, such as computer-assisted word-frequency analysis by international scholars, further aid in identifying potential authorship and redaction layers within the ancient scriptures, dating back some 2,800 years. These academic approaches underscore the dynamic and layered nature of biblical composition, moving beyond singular authorship to acknowledge a rich history of literary development and editorial intervention. This perspective acknowledges the human element in transmitting divine inspiration.

The Documentary Hypothesis and the Old Testament

The Documentary Hypothesis is a pivotal scholarly theory concerning Old Testament authorship, especially the Torah (the first five books). It asserts that the Pentateuch is not the work of a single author, like Moses, but a compilation from several distinct source documents integrated over centuries. According to this analysis, the whole Old Testament, specifically the Torah, was started around the year 1000 BCE. Significantly, it was not a static text but underwent continuously re-edited and modified for approximately 500 years. This ongoing redaction involved various authors and editorial schools contributing to and shaping the narratives, laws, and genealogies. The hypothesis identifies distinct literary strands, such as J (Jahwist), E (Elohist), D (Deuteronomist), and P (Priestly), each possessing unique linguistic traits, theological perspectives, and historical contexts. This continuous re-editing implies a dynamic evolution of the text, challenging traditional views of sole authorship and suggesting a collective, iterative process of biblical composition over an extended period, reflecting diverse human influences.

Continuous Re-editing and Modification of the Torah

The Torah, comprising the first five books of the Old Testament, did not emerge as a singular, static creation but rather underwent a process of continuous re-editing and modification. According to critical scholarly analysis, the initial composition of the Old Testament, specifically the Torah, commenced around 1000 BCE. However, this was merely the genesis, as the text was continuously refined, expanded, and altered for approximately 500 years. This extensive period of revision involved multiple authors and editorial schools shaping its content. Not all modifications were benign; they often reflected fundamental theological shifts within ancient Israelite society. Scholars inferred that the Torah originally exhibited polytheistic views, acknowledging the existence of many gods. Over time, it transitioned to monolatry, where multiple deities were accepted, but only one was worshipped. Ultimately, it evolved into a strictly monotheistic framework. This profound and ongoing evolution demonstrates the Torah was a living document, constantly adapted to reflect changing beliefs and historical and societal contexts, challenging the notion of a fixed, unchanging central message from its earliest forms and highlighting the profound and dynamic human involvement in its shaping.

Shifting Theological Views: Polytheism to Monotheism

The theological landscape within the biblical texts, particularly the Old Testament, was not static but experienced significant evolution, notably a profound shift from polytheism towards strict monotheism. Early interpretations and archaeological findings suggest that the Torah, in its nascent stages, might have been rooted in a polytheistic worldview, acknowledging the existence of multiple gods. This perspective gradually transitioned into monolatry, a practice where ancient Israelites recognized the presence of various deities but committed their worship exclusively to one specific God, Yahweh. This intermediate phase was crucial in the theological development, laying the groundwork for the eventual embrace of absolute monotheism. The continuous re-editing and modification of the Torah over centuries played a pivotal role in solidifying this monotheistic stance, systematically refining narratives and commandments to assert the singularity and supreme authority of Jehovah. This profound transformation in understanding the divine reflects a dynamic religious environment and illustrates how the “central message” was not uniformly conceived from the outset but developed and coalesced over an extended period through a complex process of theological refinement and editorial intervention. Such a shift profoundly impacted the understanding of God’s nature, role, and interaction with humanity, demonstrating a clear evolution in belief systems throughout the biblical compilation.

Challenges to a Central Message

The assertion that the Bible’s numerous authors uniformly conveyed a single central message faces substantial challenges. Scholarly analysis indicates individual writers held distinct understandings and theological viewpoints, leading to overwhelming differences across the texts that preclude a unified, consistent narrative. For example, concepts of paradise and hell diverge dramatically. The Old Testament, crucially, contains no explicit notion of an afterlife or hell, reflecting ancient Jewish beliefs that initially did not embrace such doctrines. This stands in stark contrast to Christian theology, which posits heaven and hell as fundamental tenets of eternal destiny, representing a colossal shift in core beliefs.

Furthermore, interpretations of God’s role in the presence of evil and suffering also reveal shifting viewpoints. Earlier biblical books often depict God as directly instigating hardship and using pain as divine punishment, aligning with a strict omnipotent view where nothing occurs without His consent. However, later books subtly re-frame God’s role and responsibility. These evolving theological stances, coupled with continuous textual modifications over centuries, underscore the complex, non-uniform nature of the Bible’s overarching message, challenging the idea of a singular, unchanging divine communication.

Differences in Belief: Afterlife and Hell

A significant area of divergence in belief across the biblical texts and their interpretations concerns the concepts of an afterlife and hell. Notably, the Old Testament, which forms the bedrock for both Jewish and Christian traditions, contains no explicit mention or developed doctrine of paradise or hell. Ancient Jewish communities, as reflected in these older writings, did not initially subscribe to a belief in an afterlife with distinct eternal rewards or punishments as later understood. Even today, many Jewish traditions do not embrace the concept of hell in the same manner as Christian theology.

This stands in stark contrast to Christian beliefs, where the existence of heaven (often referred to as paradise) and hell are fundamental, colossal aspects of faith, representing eternal destinies. The emergence and prominence of these concepts in later biblical books and subsequent Christian theological development highlight a profound evolution in understanding the ultimate fate of humanity. This isn’t a minor interpretive variance but a monumental shift in the core message regarding post-mortem existence, showcasing how beliefs about the afterlife have significantly differed and evolved among those who revere the Bible.

God’s Role in Evil: Shifting Interpretations

The understanding of God’s involvement in the presence of evil and suffering within the world reveals a notable evolution throughout the biblical narratives. In the oldest books, there is a clear suggestion that God is indeed a direct source of evil, pain, and suffering, often portrayed as divine instruments for the punishment of humankind. These early texts present a strictly omnipotent view of God, asserting that not a single event, including misfortune or calamity, occurs without His explicit consent or direct orchestration. This perspective positions God as the ultimate arbiter and instigator of all occurrences, both good and ill, reflecting a worldview where divine sovereignty encompasses every aspect of existence.

However, as the biblical canon progresses, a discernible shift in this theological interpretation becomes evident. Later books begin to alter the focus, moving away from portraying God as the direct cause of suffering in the same unmitigated fashion. This transition suggests a developing theological thought regarding the nature of divine justice and benevolence. While the exact nuances of this shift vary, the overarching observation points to a re-evaluation of God’s direct role in the perpetration of evil, leading to more complex interpretations of suffering, free will, and divine intervention in the human experience.

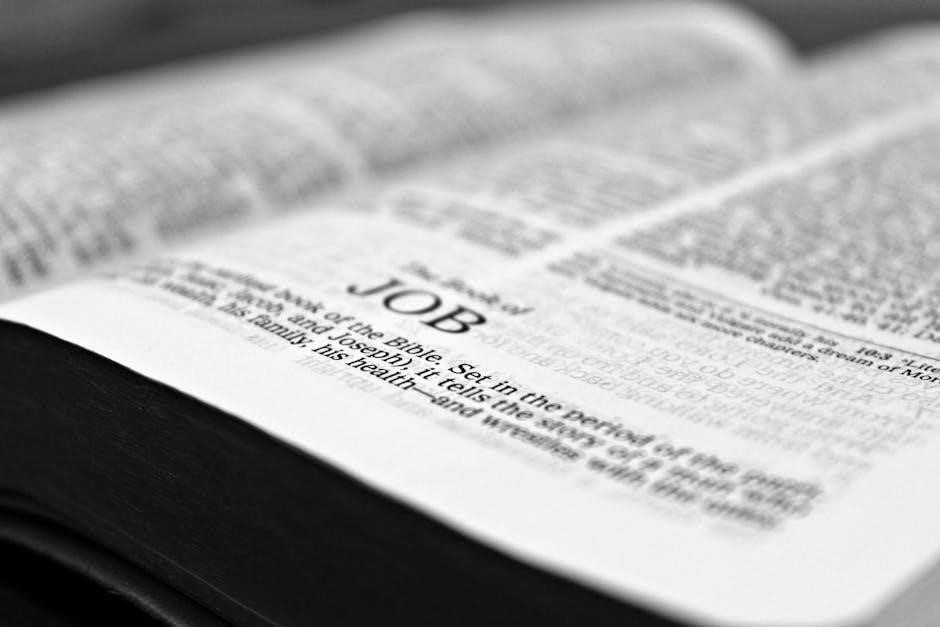

Authorship of Specific Books: The Book of Job

The authorship of the Book of Job remains a subject of considerable discussion and scholarly debate within biblical studies. Unlike many other books, Job’s origins are less certain, leading to a range of proposed candidates. Among the possible authors frequently suggested are Job himself, the narrative’s central figure, lending a powerful firsthand perspective. Other prominent figures from Israel’s history have also been put forward, including Moses, a pivotal leader and lawgiver, suggesting an early composition date. Solomon, renowned for his wisdom, is another candidate, aligning with the book’s philosophical depth. Furthermore, later prophetic figures such as Isaiah, Ezekiel, and even Baruch, Jeremiah’s scribe, have been considered, indicating potential later redaction or authorship. It is widely believed that the Book of Job is one of the oldest books in the entire biblical canon. Evidence within the text suggests that the events depicted, and possibly its initial composition, took place during the time of the patriarchs, specifically aligning with the era of figures like Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. This places its narrative context firmly in the ancient world, predating much of Israel’s recorded history as a nation. The ambiguity surrounding its writer underscores the book’s timeless and universal appeal, transcending specific historical attributions.

Compilation of the Bible: Church Councils

The compilation of the Bible into its final canonical form was not a singular event but a gradual process, heavily influenced by various church councils over several centuries. While the books themselves were penned by numerous authors across different eras, their assembly into a single, authoritative collection was a deliberate act of ecclesiastical discernment. Specifically, around 400 AD, significant church councils played a crucial role in formalizing the biblical canon. These councils, comprising leading bishops and theologians, convened to discuss and confirm which sacred writings were to be accepted as divinely inspired and thus included in the scriptural body. Their decisions were based on various criteria, including apostolic authorship or connection, widespread acceptance among early Christian communities, and theological consistency with established doctrines. This rigorous process aimed to distinguish authentic texts from apocryphal works, providing a standardized scripture for all believers. The councils’ efforts resulted in the widely recognized collection of 66 books, establishing the framework for both the Old and New Testaments as we know them today. This historical compilation underscores the communal and deliberative nature of the Bible’s formation and enduring legacy.